“Thirteen Days in October,” a 2000 Kevin Costner movie, chronicled the events in the Kennedy White House during the Cuban Missile Crisis. During the “thirteen days,” Oct. 16-28, 1962, the world came as close to the brink of nuclear war as anytime before or since. Tensions were high throughout the world and in Homewood-Flossmoor, too.

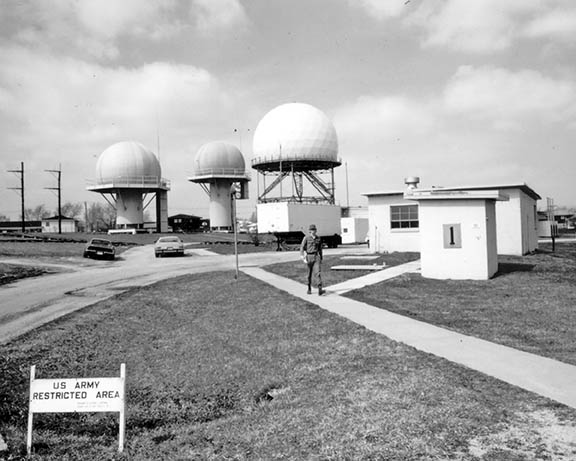

base in Homewood. The site is now Patriot Park

on 187th Street west of Center Avenue.

(Provided photo/Homewood Historical Society)

“Thirteen Days in October,” a 2000 Kevin Costner movie, chronicled the events in the Kennedy White House during the Cuban Missile Crisis. During the “thirteen days,” Oct. 16-28, 1962, the world came as close to the brink of nuclear war as anytime before or since. Tensions were high throughout the world and in Homewood-Flossmoor, too.

Locally, life went on as normally as possible, except for the activities of a battery of men working among what was still cornfields in southeast Homewood. These men were assigned to the United States Army’s 22nd Antiaircraft Group and manned a Nike missile facility, located near 191st and Halsted Street, and a companion radar facility located on 187th Street just west of Center Avenue.

During the crisis, these soldiers were on the highest state of alert and the 12 Nike missiles found here were “hot” — pointed skyward and ready to be fired — for three full days. This was the only time in the base’s existence that the missiles were raised for a real threat.

Construction of the Homewood Nike missile base, one of 23 bases that ringed the city of Chicago and the Gary steel mills, began in the fall of 1954.

On Halsted Street, where the Army Reserve Training Center is now located, three large underground concrete reinforced vaults were built to house the missiles and their launching platforms.

Unless the missiles were raised, no trace of these bunkers or their contents would normally be visible. When completed in the summer of 1955, 18 Ajax missiles were installed at the base.

Six of these first generation Nike missiles were installed in each pit and carried a conventional warhead capable of destroying a single aircraft.

Second generation Nike Hercules missiles were installed at the Homewood facility in 1959. Each vault was equipped with four of these nuclear warheads, which could target several aircraft at once. Third generation Nike Zeus missiles were never placed in Homewood.

One-half mile to the north on 187th Street, the site of Patriots Park today, the Army constructed a radar facility which could not only detect any incoming foreign aircraft but would also track the missiles once fired.

This facility included five radar platforms that were enclosed in large and distinctive white spheres shaped like golf balls. The radar site also included the headquarters and administrative offices, barracks and a mess hall.

After construction was completed, 92 officers and enlisted men of the regular army staffed the Nike units in Homewood. In 1963, civilian reservists took over operations and manned these facilities until they were deactivated in 1974.

After the Cuban crisis, the Soviets developed intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM’s) and the Nike system was incapable of dealing with this threat. Most of the 300 Nike batteries in the United States, like Homewood’s, were deactivated by 1974.

Following deactivation of the facilities in Homewood, army reserve units utilized the buildings and grounds at the radar base through 1984. That year, a new building was built for these units at the former missile base on Halsted Street. Illinois National Guard units then occupied the 187th Street buildings until they were finally abandoned in 1990.

For the next decade, the land and buildings on 187th Street remained vacant until the federal government gave them to the Homewood-Flossmoor Park District. All buildings on the site were demolished and construction of a beautiful park, appropriately named Patriots Park, was completed in 2002.

After 55 years, the only remaining vestige of Homewood’s role in the nation’s Cold War defense are the missile vaults on Halsted Street, covered with asphalt and serving as part of the Reserve Training Center’s parking lot.